Digital disruption finally made it to the physical world.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the trend to the digitization of public spaces. But it didn’t play out the way we all expected. The big digital platforms did to physical spaces what they did to every other business – transferred activity and value from the real world to the digital world.

As the economy gets going again, downtowns are still empty, and Times Square is still quiet (down 83% year over year in July). I personally do not believe the apocalyptic view that cities like New York will never be the same. People have been betting against New York City for 200+ years, and those who do get their heads handed to them.

But it won’t come easy. Twenty years of digital disruption reached Main Street. The pandemic sparked a massive shift in consumer behavior which erodes many advantages cities have had for centuries. While the pandemic will eventually end – perhaps as early as the first part of next year, many of the changes to consumer behavior are likely permanent.

To thrive in the long term, cities need to start planning for a post-COVID world now – with a focus on being desirable and affordable places to live – even if people no longer need to be there for their jobs.

Think about how daily life in America has been refactored since March 11th – the day the NBA shut down, Tom Hanks got coronavirus, and Americans recognized the scale of the crisis.

- Work. In June, more than 40% of Americans were working from home, accounting for two thirds of economic activity. With many companies keeping their offices at least partially shut for the foreseeable future, it is unlikely that we are ever going back to a world where masses of people are coming into the office five days a week. The 1.5mm commuters coming to Manhattan every day – as represented in this incredible map – is probably a lot lower going forward.

- Retail. Online shopping went from 11% to 16% in Q2. Amazon had a monster quarter, while Target and Walmart showed huge growth in their online channels. The 16% number is even bigger when you consider that restaurants, car dealerships, and gas stations account for 40% of retail sales. Given that drug stores and supermarkets account for another 20%, a large portion of the goods and services that are well suited to online purchasing are now being purchased online.

- Entertainment. Streaming services, online gaming, and Zoom chats soared during the pandemic. Netflix added 26mm subscribers in the first half of 2020. People everywhere survived not going to restaurants, concerts, and sporting events for six months and that blackout on live events will last another six months.

- Education and Health Care. The last frontiers of digitization – health care and education also got a shock. Schools everywhere moved online while telemedicine finally took hold.

While the real world economy struggled – damage was limited to small businesses and companies directly tied to public spaces – like travel, tourism, “non-essential” retail, and theaters. Unemployment was still north of 8% in August and over 20% in leisure and hospitality.

But other parts of the economy did fine. Stocks did well despite the crisis, as investors recognized that the pandemic actually drove growth for the big digital companies and essential industries already winning in the economy.

The internet stepped in and replaced many activities historically reserved for public spaces. Work from home, e-commerce, streaming, e-health and online education were happening before COVID. But the crisis made the transition go much faster and more decisively.

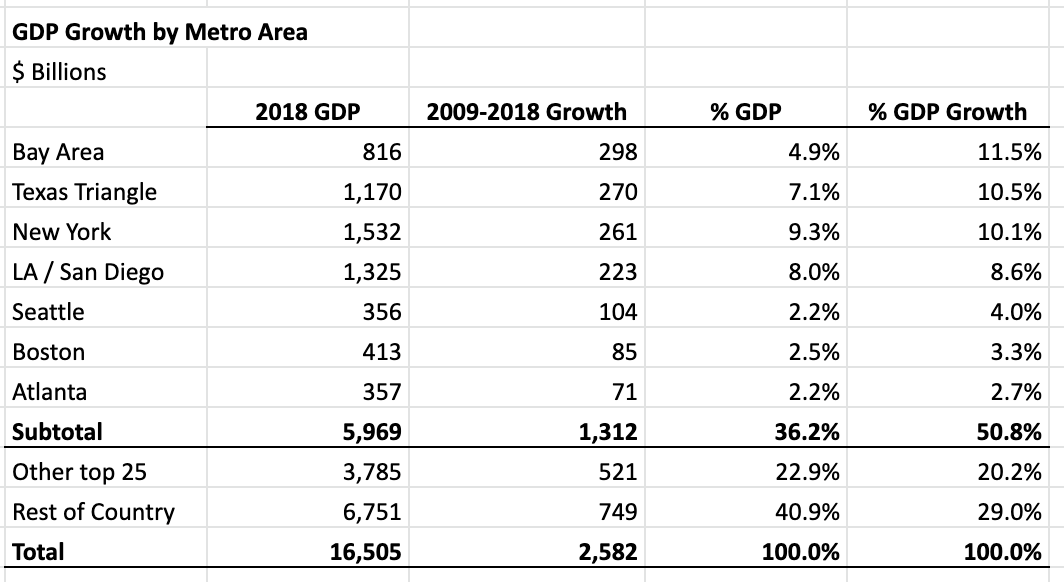

This is a big change for cities. Historically, people and businesses paid a premium to be close to economic activity. Long before the internet, network effects were driving economic growth in many great cities as industries clustered together. Superstar cities were collecting most of the economic growth. Between 2009 and 2018, seven regions (New York, LA, the Bay Area, the Texas Triangle, Boston, Atlanta, and Seattle) accounted for half of U.S. GDP growth.

Cities had a virtual monopoly on great jobs, and bundled a set of activities around the jobs. Live, work, shop, and play – all in one place, in walking or subway distance from where one lives. The “urban bundle” had a huge benefits to consumers – and helped drive a rebirth of cities.

If you don’t need to go into work every day, that benefit gets eroded. Now, you can pick the best place to live – period – with less regard to where you work. You can accept a longer commute if you have to do it less frequently. You can substitute an infrequent weekend visit to living in the city to get your live event fix. The “urban bundle” is less valuable – you pick locations as you need them.

Newspapers learned the hard way how brutal the unbundling process can be. They were cash machines when they were the only way to distribute retail and classified advertising to the home. When the internet unbundled news from ads and classifieds, newspapers were crushed. Only brands that could create content good enough that people were willing to pay for it, like the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal, could thrive.

Now cities face a similar set of challenges. The default of moving to New York to work in finance or San Francisco to work in tech is likely over. Consumers survived months without going shopping on Michigan Avenue or Rodeo Drive. Cities no longer have a monopoly on great jobs, the best shopping, the most sophisticated entertainment, or even the most influential education and health care institutions.

So how can cities bounce back? Ideally, by being affordable and desirable places to live. That means local governments need to cater to residents who live in cities not because they need to, but because they want to.

Everything starts with affordability – which means affordable housing and good public schools. It is beyond the scope of this article to tackle public education – other than to note that it is critical.

With regards to housing, it is likely most cities need to adjust their affordable housing strategies. Pre-COVID models of high end apartments with 20% reserved for affordable housing won’t work in the coming years. There’s already plenty of vacancies on the high end, and it will take years to burn off the excess supply. In the meantime, long time residents struggle to find homes.

It will be crucial to figure out a business model that creates 100% affordable developments. That may require relying more on non-profit developers in the near term and reinvesting in existing stock rather than the high end until the market rebalances – which could take many years. Community land trusts and co-ops may be a place to invest stimulus dollars to take real estate off the market and make more housing units permanently affordable.

From there, cities will need to think like the companies disrupted by the internet as they plot their comeback. Successful cities will double down on six unique advantages that the internet can’t take away.

- Walkability. Even when working from home, a walkable local neighborhood remains highly desirable. Outdoor dining, one of the few bright spots for cities in the pandemic, became a way for neighborhoods to maintain vibrant street life. Combining independent restaurants with bakeries, places of worship, independent retailers, coffee shops, beauty parlors, barber shops, and gyms, make a walkable neighborhood a great place to live and an even better place to work from home. In addition, small co-working spaces where people can “work from home” from outside their apartment may become the new go-to amenity for buildings or neighborhoods.

- Independent businesses. Unique walkable neighborhoods rely on small businesses. Lacking the scale to compete online, many of these small businesses are deeply at risk. Yelp reports that more than 175K businesses closed since the pandemic started, with nearly half of those closures permanent. The damage was worst in cities like LA, San Francisco, Chicago, and New York. Entrepreneurs will restart businesses, but cities need to make it easier and eliminate red tape. SF Mayor London Breed’s focus on streamlining the permitting and approval process is a good example of what cities need to do. More direct support will likely be required, as getting small businesses back on track has to be a top priority. Independent businesses create jobs, improve quality of life, and allow residents to build wealth.

- Parks and waterfront. Park usage in big cities has soared during the pandemic – for good reason. People needed to get out of their apartments. The need for quality public outdoor space will continue post pandemic, especially in a more work from home economy. It will be tempting for cities to pull back on their parks to save money, but few city amenities have more impact on more people at lower cost than a good local park or playground. Major landowners may have to help subsidize those efforts, like the Central Park Conservancy does in New York.

- Leisure and live events. Once the pandemic is over, there will be massive pent up demand for experiences, so live music, theater, comedy clubs, restaurants, museums, and gaming spaces will do well once the pandemic ends. Cities still have critical mass to remain experiential destinations, which will have enduring appeal to tourists, singles, and empty nesters.

- Cultural institutions. Similarly, museums, public gardens, symphonies, operas, and other cultural institutions remain a critical advantage cities have – and governments and the real estate owners need to keep these institutions afloat. Not only do they support tourism and quality of life for residents, but cultural institutions are a strategic advantage for urban public schools – which often benefit from outreach and educational programs.

- Diversity. Finally, cities have the critical mass to support a great deal of diversity – of ethnicity, faith, education, and interest. Long before Facebook Groups, people could find the group they were looking for in a city. More importantly, in physical space citizens also benefit from meeting people who they don’t seek out. Maintaining that diversity requires ensuring equitable growth policies for all neighborhoods and populations.

Much of these advantages come back to the power of individual neighborhoods. Residents and small businesses will become a bigger portion of the city economy, making affordability and livability across all neighborhoods in a city more critical than ever.

Like companies undergoing digital disruption, cities can survive and even thrive, if they focus on their residents and the unique advantages the internet cannot take away. People have always and likely will always want to congregate in cities. But why and how they come together will change, and the cities that innovate for that new reality will be the most successful ones.